(Feb 9, 2020 This post has had correction appended)

In June 2018 the Canadian federal government initiated a review of the Telecommunications and Broadcasting Acts with the intent of getting guidance on how best to integrate the realities of the internet and global communications into the existing legislation.

The project overview page with associated timeline is here.

The panel released its report on January 29, 2020, entitled Canada’s Communications Future: Time to Act

Weighing in at 235 pages, the report contains 97 recommendations for an overhaul of Canada’s internet, telecom and communications laws. The report can be viewed here you can pull down the PDF right here.

I’m not going to go through this point for point. There are a few things in there that “aren’t terrible”, according to one of my colleagues who I won’t name because we sit on a board that’s mortified at the prospect that I even mention them when I write about this. So I won’t.

From here on down I’m speaking on my own dime, opinions are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of my company, its employees, clients, nor any associations, boards, panels, working groups or forums I participate in…

The best in depth analysis coming out right now is via Michael Geist, the University of Ottawa law professor who has been immersed in all matters cyber and legal for a couple of decades now.

My take on it is for the most part is that it’s a bag of mostly crap that contains more than a few absolute, unconditional non-starters, such as requiring all producers of news content to obtain a license, and making social media sites responsible for the content that traverses or resides on their networks and platforms:

Recommendation 56:

We recommend that the existing licensing regime in the Broadcasting Act be accompanied by a registration regime. This would require a person carrying on a media content undertaking by means of the Internet to register unless otherwise exempt. Those carrying on a media content undertaking by means other than the Internet would continue to require a licence unless otherwise exempt.

Recommendation 54:

We recommend that the Broadcasting Act apply to media content undertakings involved in the creation and distribution of media content. The term “media content undertaking”, which would replace the term “broadcasting undertaking” in the Act, would include media curation undertakings, media aggregation undertakings, and media sharing undertakings, as follows:

Media curation undertaking means an undertaking whose primary purpose is to provide a service for the dissemination of media content over which it exercises editorial control […]

Media aggregation undertaking means an undertaking that, in whole or in part, provides a service that aggregates and disseminates media content provided by media curation undertakings.

Media sharing undertaking means an undertaking that, in whole or in part, provides a service that enables users to share media content for which the provider does not have editorial control but which the provider organizes or controls.

And tucked into Recommendation 53 which otherwise talks about inclusivity, diversity, CanCon, yada yada yada, oh and also….

Media content undertakings should have a responsibility for the media content they provide.

Yikes. My read on this is that any web sites whose primary purpose would indeed be to “provide a service for the dissemination of media content” would according to these recommendations be “a media curation undertaking”, and thus as a media content undertaking (Recommendation 54) and have responsibility for the content hosted on their platforms.

This puts an onus on the likes of Facebook, Twitter, or any smaller, startup platform including anybody operating a forum or a Mastodon instance, to police the user posted content on their platforms. Social media platforms policing content is already a huge problem in that they tend to project their own biases into their AUPs. Enforcement is inconsistent, appearing at times to be whimsical. To mandate responsibility to the platforms would amplify the problem and curtail the free speech rights of many.

On the media production side, content creation, the recommendations explicitly stipulate that alphanumeric content, which means articles, essays, anything in the written word, becomes a type of “news content” and thus creators would be required to register and obtain a license.

Last weekend, Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault went on national TV to say, yes, this would mean content creators would need to be licensed, but he didn’t see it as a big deal, expecting it to have “proportionality”, whatever that means.

A panel commissioned by @JustinTrudeau has recommended that news websites ad podcasters in Canada be required to get a government licence. Unbelievably Trudeau’s Heritage Minister @s_guilbeault agrees with the idea. So much for a free and open media.

pic.twitter.com/azwC8sDg55— Brian Lilley (@brianlilley) February 2, 2020

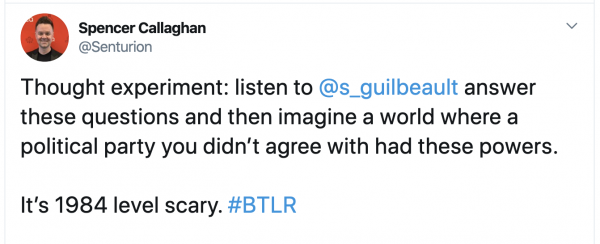

That set off a violent shitstorm of bile across the mediasphere,

Agreed. https://t.co/gXtC0jueV3

— Mark E. Jeftovic (@StuntPope) February 3, 2020

Interesting. And who would grant such a license? Why, the government that wants to control the message! I guess the $600 million media payoff isn’t working as planned.

— ken comeau (@dadkc66) February 2, 2020

By Monday, he had to walk that back:

“Let me be clear, our government has no intention to impose licensing requirements on news organizations, nor will we try to regulate news content. We are committed to free and independent press, which is essential to your democracy,”

Still, it was dangled, and the recommendations are there in the report, and they could easily weasel on Guilbeault’s pledge by qualifying what “news organizations” are, possibly when they get around to defining what “unlawful content” is (see below).

There are still plenty of other recos to be worried about, in no particular order:

- Foreign streaming services will be required to collect and remit GST/HST (#85)

- CanCon will apply to all broadcast and communications mediums, whether you think that’s a good thing or a bad thing (I always thought it was unnecessary, even my prior incarnation as a failed musician).

- CBC will eliminate advertising within 5-years, starting with the news shows, so I guess that would have to mean more taxpayer funding to keep it going.

- Extension of the Broadcasting Act to regulate not only audio/visual content but all content including “alphanumeric news content” made available by any public means. (#51)

- Regulation of the economic relationships between media outlets and content producers, including terms of trade (#61)

- CRTC given power to collect consumption data from media outlets to publish in aggregated form (#64) (If you’re a subscriber to Jesse Hirsh’s Metaviews then his latest column on how anonymized aggregated data is increasingly not anonymous is of interest)

- Making digital providers liable for content (#94)

- Review of how the government monitors and enforces the takedown of illegal content (#95)

Like I said, there are 97 of these.

Regulating Content not Mediums

No matter how the government tries to soften it, the overall tone and stated goal of the report by its own words is a new model where the regulatory framework is hardware agnostic and shifts focus to content:

Our new model is platform agnostic and technology neutral. It focuses on the activities being carried out and establishes consistent obligations to support Canadian cultural policy for all media content undertakings involved in similar activities.

(emphasis added)

The phrase “lawful content” appears in the report, it is not defined, but its mere presence bothers me immensely,

we also recommend that an explicit policy objective be added to the Telecommunications Act to affirm a user right to an open Internet – in which lawful content can be accessed anytime, from anywhere – in order to ensure freedom of speech and innovation

That paragraph doesn’t actually signal an intent to ensure your freedom of speech. What it actually does, is it bisects content into the categories of “lawful” and “unlawful”, with the definitions of what that means to be defined later, one would presume.

The phrase “illegal content” appears four times in the report, including section 4.5 headed “Illegal content and conduct”

Illegal content and conduct are related to, but distinct from, harmful content and conduct. They include behaviours that violate a wide range of laws, including child exploitation and abuse, terrorist content and activity, hate crimes, incitement of violence, sale of illegal products or services, cyber violence, harassment and stalking, or non-consensual sharing of intimate images.

“Harmful content” appears six times in the report, under the heading “A Focus on Users” the impetus is:

Central to all our recommendations is a desire to better position users of communications services…

whether we are talking about access to broadband, access to media content, including diverse, trusted and accurate sources of news content, safeguards against privacy breaches, Big Data or harmful content.

Again, harmful content is not defined, but given that the report pines for “accurate sources of news content” I’m willing to be that if this moves forward, we would see some sort of attempt to codify it that would include the Fifth Horseman of the Infopocalypse, Fake News.

Recommendation 73: We recommend that to promote the discoverability of Canadian news content, the CRTC impose the following requirements, as appropriate, on media aggregation and media sharing undertakings:

(emphasis added)

Fake news could include all manner of that there “unlawful content” such as any alphanumeric text that doesn’t conform to official narratives emitting from “Approved Media”.

Why is Canada’s Big Media so Quiet About BTLR?

When giant, incumbent companies are silent about impending regulation, or, are actively encouraging new regulation, it isn’t out of an altruistic desire to level the playing field.

It’s usually to widen the moat against rising competitors and to further ensconce themselves into a de facto monopoly. As I like to describe it:

Regulation for thee =

Monopoly for me…

Michael Geist documented Bell’s submission to the BTLR panel, details which he had to obtain through a Access to Information request, and found it to be:

self-serving in the extreme: higher wireless and entertainment costs for consumers, competitive advantages for Bell, … harms to net neutrality, and an extensive regulatory system aimed at Bell’s competitors

A former CTRC commissioner put Canada’s Big Media silence on #BTLR to me like this:

The large cable companies have in the past indicated that they carry a regulatory burden others don’t so to that extent I expect they would be happy to have their competition carrying the same weight. The newspapers may be quiet because they see the possibility of having social media ad revenue redirected to them in exchange for their independence.

If BTLR is going to be stopped, we aren’t going to get any help from Canada’s media oligopoly. We’ll have to do it ourselves.

The Petition to Reject BTLR Entirely

As I said off the top, there may be some stuff in there that “isn’t terrible”. However, overall the report issued is so flawed that any legislation or reorganization of the regulatory framework resulting using BTLR as a basis will be irredeemably problematic for free speech, net neutrality and an open internet.

The impetus toward licensing free speech, and opening the door toward marginalizing dissenting views as harmful or unlawful content are extremely troubling.

Given the rampant official and non-official increase in deplatformings and cancel culture in general (phenomenon’s we cover in our weekly #AxisOfEAsy newsletter and in my recent book on the subject) any government sponsored legislative work has to enshrine free speech, not put conditions around it.

To that end, a petition has been introduced to the House of Commons, put forth by myself and sponsored by MP Michael Chong, the Shadow Minister for Democratic Institutions. We have until June 5th, 2020 4:13pm to get enough signatures on it to compel the federal government to respond.

Sign petition E-2418 now, and then share this article, tag your messages with #killbtlr and or use killbtlr.ca

Help Get the Word Out

- Upvote on Hackernews

- Upvote on Slashdot

- Share via the buttons below

Correction

It has been pointed out to me that I was wrong about the framework calling for ISPs to be responsible for content traversing their network, my confusion was that the definition of “media content undertaking” included anybody providing the capability to disseminate content. However I somehow did miss that this is specifically addressed in the report:

In their submissions to us, stakeholders were also divided as to whether definitions should be modified to extend the application of the Broadcasting Act to ISPs. In our view, access services should be excluded from the ambit of the Broadcasting Act. As carriers, ISPs should contribute to carriage, connectivity, and universal access — as recommended earlier in chapter 2 of this Report — rather than content.

One frustrating thing about the Internet is that people tend read something, often without context or background, then react to it in almost hysterics. This then attracts other people to pile in either attacking the source, or the person (now people) in hysteria about it. And just like that, you have an internet knife fight involving thousands.

Then, eventually everyone calms down a bit. The details are clarified and the real issues are distilled and the original problem gets ironed out to a more acceptable level.

Except for a small group who will never accept the outcome and who will, even when either shown to be wrong, or when the underlying issue has gone away, will continue to misrepresent facts and ‘rage against the system’.

So, onto this particular knife fight. First off, we’ve been here before. Many times – specifically WRT copyrights. The government kept trying to bring in DMCA like amendments to the Copyright Act and everytime they took it to the public, the public said ‘f*** that’ and we still don’t have anything as draconian as the DMCA here.

We do end up with some bizarre compromises (see: Audio CD Levy which became sort of irrelevant less than a year after it finally got implemented, so they tried to apply it to DVDRs and then hard drives… to no real avail).

So let’s back up a bit. There are a few main goals here.

1. Impose some form of legal infrastructure on the Internet in terms of legal or illegal content. It’s easy to sneer at the phrase ‘illegal content’, but here’s a simple example: child pornography. I think most of us would agree that it should be illegal content.

2. Enforce the copyright act. Canada is a member of the Universal Copyright Convention, as are most western nations, although we do have one of the loosest and pro-consumer versions of it. Nonetheless, we do have an obligation to enforce it.

3. Canadian content. This is one of the oldest mandates of the CRTC – to ensure that Canadian culture and opportunities are not lost in a flood of content from wealthier nations. Usually that’s the US, but on the Internet, there’s a tendency to favour one nation over the other, so the UK tends to ignore Canada over Australia, for example. The US tends to go UK then Europe then India or Australia.

Each of the provisions listed is an attempt to implement one of these goals.

Technically, if the Internet were a Canada only thing, all of this would make perfect sense. The ‘free speech’ argument would make no more sense here as it would a company like Netflix being obligated to make CanCon or a magazine having to pay to use photographs or newsarticles from other sources. That aspect of it isn’t really controversial.

Where it does become so is that the Internet is NOT ‘Canada only’ and so simply isn’t open to being regulated like that. Every attempt to do so has failed and has led to new ways to hide on the Internet.

In the end, I think it’s simpler to accept that this document isn’t a blueprint for new laws.. it’s a discussion paper on options. It will have to go before committees who will then ask ‘can this be done?’ and ‘should this be done?’ A modified version of it will eventually be opened for public input and knowing Canadians, it will be savaged and either highly minimised (like repeated attempts to strengthen the Copyright Act) or outright abandoned (like Harper had to with his attempt at it).

I’m not saying ‘don’t worry about it’, but I am saying ‘don’t panic’.

BTW, Twitter and Facebook are NOT media aggregation services. We’ve actually already had that discussion while trying to amend the copyright regime. That’s a misinterpretation of the concept. It refers to sites which basically go out and collect news or content created by other people into one site. That’s the whole idea behind ‘curated’. Facebook and Twitter aren’t ‘curated’ outside of broad restrictions against content that might be deemed illegal.

Even a site that reports on articles on other sites isn’t necessarily a news aggregator depending on how it reports the other news. On the other hand, things like Google News and MSN ARE aggregators and make money by simply collecting articles around the Internet, using a little AI to classify them then use user profiles to feed articles in order to increase click-through rates which net them revenue at little cost or effort, often denying the original creator any revenue in the process by blocking their ads.