The scale and immensity of hacking incidents worldwide is on the upswing. It seems everybody is getting hacked at one point or another. Even easyDNS had a low level data breach a few months ago (email addresses were exfiltrated from a server housing a third-party marketing CMS).

The scale and immensity of hacking incidents worldwide is on the upswing. It seems everybody is getting hacked at one point or another. Even easyDNS had a low level data breach a few months ago (email addresses were exfiltrated from a server housing a third-party marketing CMS).

Some incidents are worse than others, and the severity of a breach is heavily influenced by the security regimen under the hood of a given vendor.

Which brings us to the reason I’m posting today. A security list I’m on regularly analyzes data dumps of various breaches around the world so that security researchers can learn about hacking patterns and IT ops personnel can take defensive measures for their users.

One of the worst breaches of late was the 000webost.com hack, in which 13 million account credentials were dumped onto the internet, and it turns out that user passwords were stored in their system in cleartext.

What this means

It means that even if you personally employ a strong password, an unguessable password, a password so inscrutable your own spouse would never figure it out, and it was so good that you used it in multiple logins; then that password would be useless if just one vendor stores that password in the clear and then gets compromised.

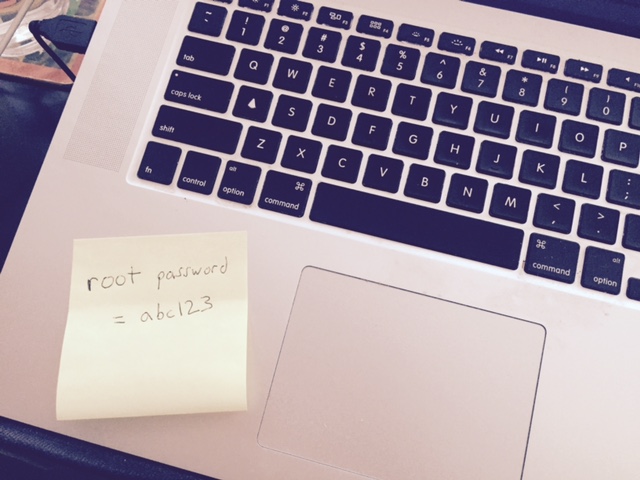

Once that were to happen your password would be visible for all to see and it may as well be “abc123” (which happens to be the actual password used by 37,073 users in the 000webhost data dump I’ve been analyzing, roughly 1/4% of passwords).

It gets worse

You may think that since your password is “so good” that nobody will ever guess it and it would take a rainbow hash 50 years to compute it, you’re safe. But if the aforementioned scenario plays out you would be less than safe if you didn’t know that your password had been compromised.

That’s why we’ve been comparing the passwords found in the 000webhost data breach against our own user’s database.

It turns out that 2,390 easyDNS members also had 000webhost accounts.

Out of those users, 248 of them have the exact same password here as they were using there (we don’t store passwords in the clear, but we can tell by comparing the encrypted hashes of the cleartext passwords).

Those affected users’ passwords are sitting on the Internet, in the clear and anybody who knows enough about the hacker back alleys of the web could find that information and use it to log into any other account across which those passwords have been reused. (We’ve already reset the passwords on all accounts found to have the same password, so they won’t work here).

What do you do about it?

Ideally you want to set things up so that even in the event of a password compromise, you still have a degree of insulation from disaster.

Using easyDNS Security Tools to the Fullest

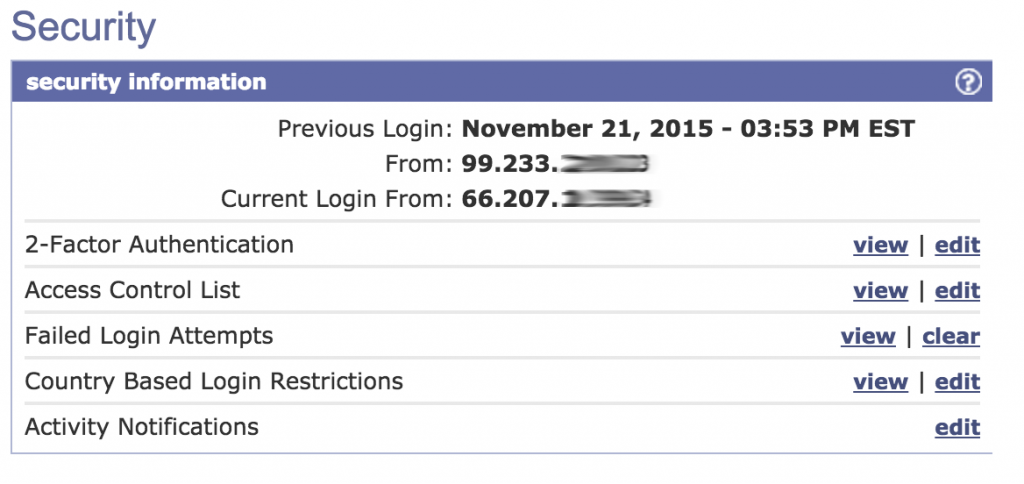

There are numerous security features you can enable on your account to mitigate a possible compromise:

- Enable 2-factor authentication

- Impose an Account ACL

- Turn on all account Event Notications

- These are all configurable under your account Security Preferences.

Employing Better Security In General

If you’re not already, you have to start using strong passwords, unique to each website you use. Which can be daunting and possibly crippling unless you have a coherent and secure methodology for organizing and retrieving those password.

Enter: multi-factor authentication systems. These systems store your passwords, in an encrypted form and you use one password to access and decrypt the central store. Obviously, you want to employ best practices to safeguard this one password (setting it to “abc123” not recommended), such as enabling 2nd factor authentication to log in (if the system supports it)

There are commercial systems such as Lastpass and 1password. Many of these offer a free level of service for personal use and premium features for enterprise. (Enterprise capabilities make it easier to implement a password regimen across your organization, such as maintaining shared folders split across various departments, designating certain passwords as “login only” – meaning the end-user can’t actually see the password, and adding additional security challenges to specific logins).

Open source alternatives also exist such as KeePass and Encryptr.

Conclusion

The important point to get is that if you’re not already using some kind of multi-factor authentication to secure yourself online, you’re only as secure as your weakest vendor.

We will continue monitoring breach data as much as possible to scan for signs that customer credentials have been compromised elsewhere, but we’d feel a lot better about it if we knew everybody had taken steps to secure their online credentials.

Further Reading

Password Manager Systems

- LastPass (or try their Enterprise free trial)*

- 1password (mobile version)*

- Keepass (open source)

- Encryptr (open source)

- Password Safe (recommended by members)

- Wikipedia list of password managers

* these links are using an easyDNS referral code

Having a unique password per service is a good start. I'm going a bit further: A unique pair of email address and password per service. For this I'm using a special sub-domain, a catch-all rule and a random character string as mailbox name to uniquely identify a single service.

Benefits? Exploiting captured credentials is more difficult. You cannot know if the address matches exactly or even if a sub-string of the address identifies a unique victim.

Although obscurity never replaces security it raises the threshold of success for potential attackers. If you are using KeePass already and have your own mail domain then providing an unguessable email address per service is almost no additional work.

I've thought for years that there is a simple technique that could be use to defeat brute-force password attacks. Include in every account profile a counter of the number of login failures since the last login success; call it "N". Then when a login fails, increment the counter, wait 2**N seconds before responding with the failure message, and ignore any other login attempt during this wait period. The exponential delay will not bother a genuine user who is just having a fumble-fingered day, but it would effectively block any automated brute-force attack. A little sophistication could be added in order to be nice to the fumble-fingered user who happens to attempt login after a brute-force attack has been tried.